Barrett's esophagus is the only known precursor to esophageal adenocarcinoma

Individuals with [.text-color-brand-blue][#tip-1]Barrett’s esophagus[#tip-1][.text-color-brand-blue] are at an elevated risk of developing [.text-color-brand-blue][#tip-2]esophageal adenocarcinoma[#tip-2][.text-color-brand-blue] – an esophageal cancer. The incidence of this once rare cancer has increased by more than 500% since the 1970s. Esophageal adenocarcinoma is highly lethal after symptoms emerge, with less than 20% of patients surviving for five years after symptom onset. Therefore, cancer prevention is key. Because the only known precursor to esophageal adenocarcinoma is Barrett’s esophagus, treatment of high-risk Barrett’s esophagus patients is the best way to prevent esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Barrett’s esophagus itself is not harmful, and only a small percentage of people with Barrett’s esophagus will ever develop cancer. However, given the lethality of esophageal adenocarcinoma, and the success of Barrett’s esophagus treatment, clinical guidelines recommend treatment of individuals with Barrett's [.text-color-brand-blue][#tip-3]esophagus[#tip-3][.text-color-brand-blue] with an elevated risk of developing cancer. Those with a very minimal risk of cancer progression do not need treatment, but will undergo regular endoscopic surveillance. Barrett’s esophagus screening – which identifies individuals at risk of developing cancer – is, therefore, key to the treatment and management of Barrett’s esophagus.

Barrett’s esophagus progression to cancer

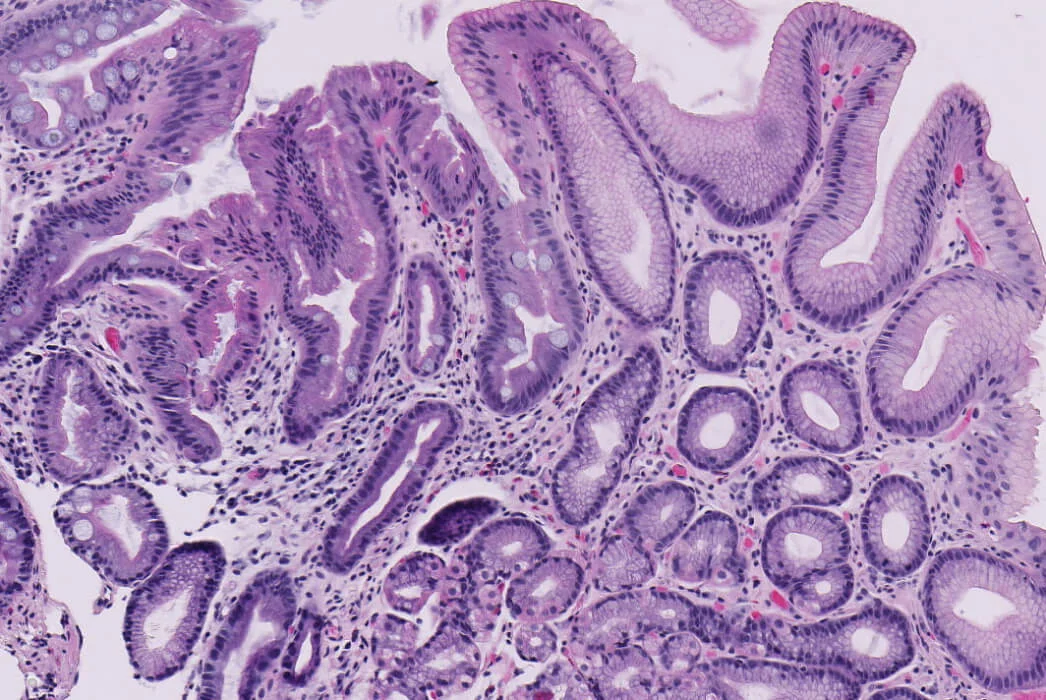

Barrett’s esophagus is thought to progress sequentially from inflammation to metaplasia (a change in cell type), dysplasia (abnormal cell growth) and cancer. Barrett’s esophagus treatments intend to treat any dysplastic cells before cancer develops. During endoscopic surveillance, clinicians identify and biopsy suspected Barrett’s esophagus. Pathologists will analyze these biopsies in order to diagnose the condition and determine the presence and degree of dysplasia, which is used to grade an individual’s risk of progression to cancer. Molecular changes in Barrett’s esophagus tissue can also precede and accompany the development of dysplasia or cancer. Clinicians turn to TissueCypher to get an independent assessment of cancer progression risk based on predictive cellular, molecular and morphological information.

.8bdff727.png)

Barrett’s esophagus dysplasia

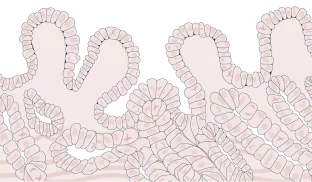

Dysplasia is when the shape, size and organization of cells are abnormal. In dysplastic cells, large and irregular nuclei develop and become displaced from their normal position.

Dysplasia grading

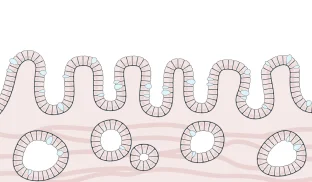

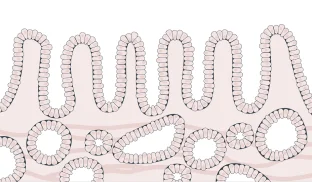

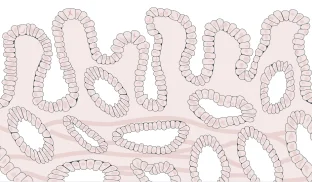

Because Barrett’s esophagus is a [.text-color-brand-blue][#tip-4]precancerous[#tip-4][.text-color-brand-blue] condition, it is graded by presence and severity of [.text-color-brand-blue][#tip-5]dysplasia[#tip-5][.text-color-brand-blue], but not staged. Dysplasia is when the shape, size and organization of cells are abnormal. In dysplastic cells, large and irregular nuclei develop and become displaced from their normal position. Dysplasia is graded (or classified) as high-[.text-color-brand-blue][#tip-6]grade[#tip-6][.text-color-brand-blue] (HGD), low-grade (LGD) or indefinite (IND), while those with no dysplasia have non-dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus (NDBE). Higher grades of dysplasia have the highest risk of progressing to cancer.

- Annual cancer progression risk: < 0.3% (1 in 333)

- Five year risk for either HGD or cancer: 0.63% (1 in 159)

- Cells have normal shape, size and organization

The vast majority of patients diagnosed with Barrett’s esophagus do not have dysplastic cells. On the whole, patients with non-dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus are at low [.text-color-brand-blue][#tip-8]risk of progression[#tip-8][.text-color-brand-blue] to cancer, but true risk varies individually and some are actually at high risk. Because this group is so large compared to patients with dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus, those initially diagnosed as non-dysplastic still make up 50% of patients who progress to cancer every year.

- Annual cancer progression risk: 0.6% (1 in 167)

- Five year risk for either HGD or cancer: 1.5% (1 in 67)

- Cells may be dysplastic, but the [.text-color-brand-blue][#tip-9]pathologist[#tip-9][.text-color-brand-blue] is not certain

In 4% to 8% of biopsies, the presence of dysplasia may be hard to determine with certainty, often because morphological changes associated with less-advanced dysplasia are so small, and may be difficult to distinguish from inflammation. pathologists will grade an individual as “indefinite for dysplasia” if it is unclear whether the cells are dysplastic or not. Patients that are indefinite for dysplasia receive a follow-up endoscopy after an attempt to reduce inflammation and reflux through medication.

- Annual cancer progression risk: 0.5% per person, per year (1 in 200)

- Five year risk for either HGD or cancer: 1.7% (1 in 59)

- Cells are beginning to grow abnormally, but not yet likely to become cancerous or spread

Grading low-grade dysplasia can be very challenging, and pathologists often do not agree on the diagnosis. To reduce the uncertainty in grading, a pathologist will get a second opinion from another expert pathologist if abnormal changes are suspected but the biopsy is not clearly precancerous. Up to 85% of low-grade patients are downgraded to indefinite for dysplasia or negative for dysplasia upon expert pathology review.

- Annual cancer progression risk: 6.6% to 10% (1 in 10-15)

- Cells are growing abnormally and are precancerous

The cellular appearance of high-grade dysplasia may be indistinguishable from that of cancerous cells. Unlike a diagnosis of indefinite or low-grade dysplasia, high-grade dysplasia does not require confirmation by another expert pathologist. Patients will almost always receive treatment for high-grade dysplasia.

Risk of progression depends on several factors

Patients with high-grade dysplasia can immediately be flagged for treatment because they have a clear elevated risk of progression to cancer. However, the decision to treat Barrett’s esophagus, or to monitor the condition for future risk, becomes more nuanced for individuals with less advanced dysplasia or no dysplasia at all. Many people are either at much higher or lower risk of progression than their dysplasia grading suggests. For example, one patient with non-dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus develops cancer within a year of diagnosis, while another non-dysplastic patient remains cancer-free for decades. This variability in outcomes makes determining appropriate patient care very challenging.

For patients with low-grade dysplasia, or who are negative for dysplasia, accounting for additional factors that contribute to an individual’s risk of progression can help to determine appropriate treatment and management. Just as sleeping well and studying before an exam are more powerful in combination, Barrett’s esophagus risk factors are additive, and are considered in conjunction with dysplasia grading to predict an individual’s risk of progression.

Many of the risk factors for developing Barrett’s esophagus – such as age, weight, gender, hiatal hernia and family history – are also risk factors for developing cancer. Other risk factors of cancer progression, such as the presence of lesions, are identified during the endoscopic screening or biopsy analysis.

Segment length in Barrett’s esophagus

One risk factor of progression to Barrett’s esophagus is segment length, which is how far up the esophagus the intestine-like tissue extends. Treatment guidelines subdivide patients with non-dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus by segment length and recommend those with short-segment Barrett’s esophagus receive follow-up screenings less frequently than those with long-segment Barrett’s esophagus. However, the progression risk associated with long-segment Barrett’s esophagus is not high enough to reliably identify non-dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus patients who are the most likely to progress.

Factors contributing to cancer risk

Increasing precision in risk assessment

TissueCypher, allows clinicians to look at [.text-color-brand-blue][#tip-7]molecular changes[#tip-7][.text-color-brand-blue] in Barrett’s tissue that predict the risk of progression. These changes can precede morphologic changes used in dysplasia grading, and are powerful independent predictors of progression risk.

A Mayo Clinic pooled analysis showed that TissueCypher was a stronger predictor of progression to high-grade dysplasia or to esophageal adenocarcinoma than any other risk factor (age, hiatal hernia, segment length, sex, low-grade dysplasia) (Iyer et al., 2022). Another study, SPaT, found that non-dysplastic patients with a high-risk TissueCypher score progressed to cancer more often than Barrett’s esophagus patients with low-grade dysplasia, with an annual cancer progression risk of 6.9% (1 in 14) (Frei et al., 2020).

TissueCypher is an AI-driven, precision medicine test to predict the risk of progression from Barrett’s esophagus to cancer. Learn more about how TissueCypher is informing personalized care of patients with Barrett’s esophagus.