Diagnosis and screening for Barrett’s esophagus

[.text-color-brand-blue][#tip-1]Barrett’s esophagus[#tip-1][.text-color-brand-blue] is visually confirmed by performing an upper GI endoscopy or EGD (esophagogastroduodenoscopy). During the endoscopy, a [.text-color-brand-blue][#tip-2]gastroenterologist[#tip-2][.text-color-brand-blue] visually inspects the inside of the [.text-color-brand-blue][#tip-3]esophagus[#tip-3][.text-color-brand-blue] and looks for changes in the lining that indicate Barrett’s esophagus. If these changes are detected, the clinician will conduct a series of biopsies by taking small samples of the suspected Barrett’s tissue from the esophagus. These tissue samples are examined by a [.text-color-brand-blue][#tip-4]pathologist[#tip-4][.text-color-brand-blue] who makes the official diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus and looks for signs of cancer or abnormal [.text-color-brand-blue][#tip-5]precancerous[#tip-5][.text-color-brand-blue] changes known as [.text-color-brand-blue][#tip-6]dysplasia.[#tip-6][.text-color-brand-blue]

Identification of dysplasia can be a strong indicator of elevated risk for progression to esophageal cancer ([.text-color-brand-blue][#tip-7]esophageal adenocarcinoma[#tip-7][.text-color-brand-blue].) However, the vast majority of patients with Barrett’s esophagus have no signs of dysplasia. Traditionally, these non-dysplastic patients are considered to be at low [.text-color-brand-blue][#tip-8]risk of progression[#tip-8][.text-color-brand-blue] to cancer. However, some non-dysplastic patients do progress. TissueCypher can identify [.text-color-brand-blue][#tip-9]molecular changes[#tip-9][.text-color-brand-blue] that can precede dysplasia and determine a patient’s individualized 5-year risk of progression to help inform appropriate treatment and management.

What does the clinician do during a Barrett’s esophagus screening?

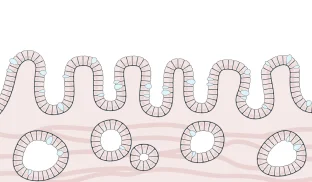

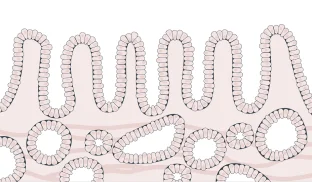

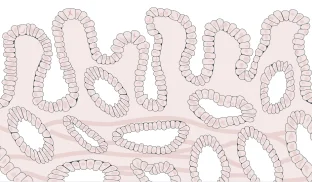

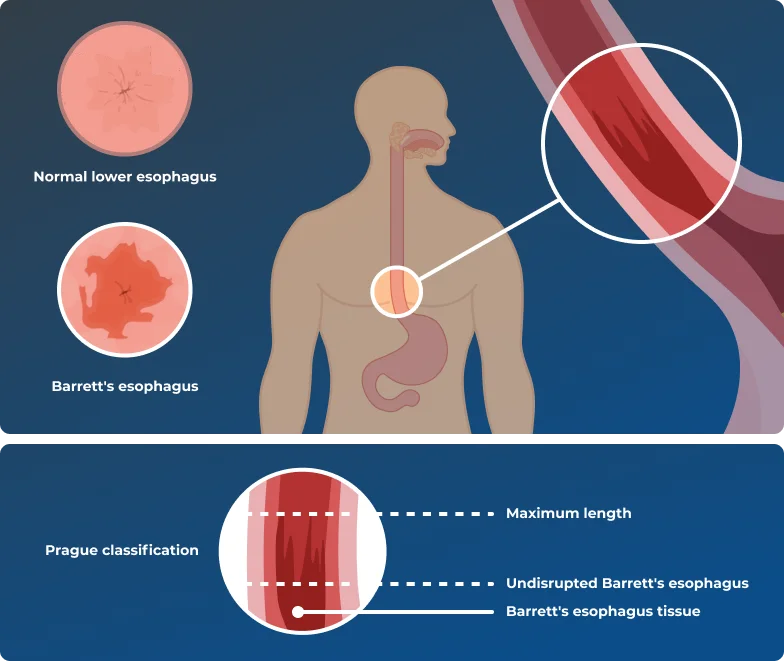

During an upper endoscopy, a clinician examines the entire length of the esophagus with a tool called an [.text-color-brand-blue][#tip-10]endoscope[#tip-10][.text-color-brand-blue] to look for changes in the esophageal tissue’s appearance. While normal esophageal tissue appears pale and glossy, Barrett’s esophagus tissue appears pink or red and velvety, which is normally seen in intestinal tissue. If these changes are detected, the clinician will insert small surgical tools through the endoscope to take a series of biopsies (tissue samples) from the esophagus.

Learn more about the methods of biopsy collection and analysis.

The clinician will also measure the length of abnormal tissue, starting from where the esophagus meets the stomach, using a method called the [.text-color-brand-blue][#tip-11]Prague classification.[#tip-11][.text-color-brand-blue]Prague classification measures both the length of undisrupted Barrett’s tissue and the maximum length that tongues of Barrett’s tissue extend upward from the stomach.

Long vs short segment Barrett’s esophagus

Barrett’s esophagus is classified as either long- or short-segment, based on how far up the esophagus the longest tongue of Barrett’s tissue extends. Patients with long-segment Barrett’s esophagus are considered to be at slightly higher risk of progressing to cancer.

The clinician will also measure the length of abnormal tissue, starting from where the esophagus meets the stomach, using a method called the Prague classification. Prague classification measures both the length of undisrupted Barrett’s tissue and the maximum length that tongues of Barrett’s tissue extend upward from the stomach.

Learn more about Cancer Risk and Dysplasia Grading.

Barrett's esophagus segment length

≥ 3 cm

Long-segment Barrett’s esophagus ≥ 3 cm

< 3 cm

Short-segment Barrett’s esophagus < 3 cm

< 1 cm

Ultra-short segment Barrett’s esophagus < 1 cm

What does the pathologist look for in a Barrett’s esophagus biopsy?

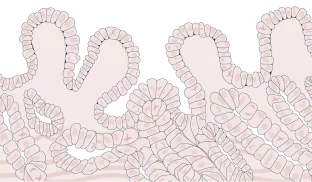

The biopsies of esophageal tissue taken during endoscopic screening for Barrett’s esophagus are sent to a pathologist for examination. The pathologist will view the biopsies under a microscope to confirm the change in cell type that characterizes Barrett’s esophagus, and grade the degree to which the structure or shape of the cells are abnormal – or dysplastic. The presence and severity of dysplasia is used to assess a patient’s risk of progression to cancer, which informs their management and treatment.

It can be difficult to correctly identify low-[.text-color-brand-blue][#tip-12]grade[.text-color-brand-blue][#tip-12] dysplasia, especially when there is inflammation of Barrett’s esophagus tissue. If a biopsy shows precancerous changes that suggest low-grade dysplasia, it will be sent to a second expert pathologist for confirmation. Up to 85% of low-grade patients are downgraded to non-dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus upon expert pathology review.

Dysplasia grading

Learn more about the methods

of biopsy collection and analysis.

Individualized risk of progression

The majority of patients diagnosed with Barrett’s esophagus are non-dysplastic and are considered to be at low risk of progressing to cancer. However, not all of these patients have the same true progression risk. A subset of people will progress to cancer, while the majority of patients never will. Further stratifying these non-dysplastic individuals to better reflect their true risks of progression requires consideration of other relevant risk factors.

Molecular information can serve as a powerful early indicator of true risk, especially in non-dysplastic patients. To get a more precise assessment of an individual’s risk of progression, clinicians turn to TissueCypher, which uses tissue biopsies to extract predictive cellular, molecular and morphological information that would otherwise not be accounted for. TissueCypher synthesizes this predictive information into a composite risk score, which can then be used to tailor the management and treatment of Barrett’s esophagus. Learn more about TissueCypher.